Behind the smoke and mirrors: demystifying misdirection

Misdirection - the art of overt & covert psychological secrets

Misdirection

Misdirection’s conjuror psychological mind scientific philosophical psychology misdirect slydini theoretical Misdirection distraction conflict of interest art misdirect mconcept theory conversation mercadian masques misdirection taxonomies magic attention magician misdirections magicians audience card example power entertainment learner arts reasoning creative thinking penn and teller color lighting apollo robbins masterclass eyeline match entertainment learner arts reasoning creative thinking penn and teller color lighting misdirection apollo robbins masterclass effect kuhn misdirect science spectator great attentional terms events learn interest wrong taxonomy cards principles coin visual citation recent perception question memory cost mind mystery psychological secret distraction questions performance methods someone Wiseman Lamont technique course reality definition effective paper noun deception gaze watch present rules manipulating spectators illusion remember mislead forms master powerful character wonder secrets analysis advanced Lamont and Wiseman perceptual examples misdirect tools friends modern ability principle deck model choice decks definitions effects correct stage cognitive sense distract martinez objects grammar inattentional misdirect cambridge medicine role scientific seem perfect scene sleight classic tatler perform movements concepts spells focused expectations to look seems misdirected misdirection’s conjuror psychological mind scientific misdirect philosophical psychology slydini theoretical Misdirection distraction conflict of interest art Misdirect mconcept theory conversation mercadian masques taxonomies magic attention magician misdirection magicians audience card example power mislead effect kuhn science spectator great attentional terms events learn interest wrong taxonomy cards principles coin visual misdirection citation recent perception question memory cost mind mystery psychological secret distraction misdirection questions performance methods someone Wiseman Lamont technique misdirection course misinformation trickery reality misdirection definition effective paper noun deception gaze watch present rules manipulating spectators illusion remember involves forms master powerful character wonder secrets analysis advanced Lamont and Wiseman misdirection perceptual examples tools friends modern ability principle deck model choice decks definitions effects correct stage cognitive sense distract martinez objects grammar inattentional misdirection cambridge medicine role trickery scientific seem perfect scene sleight classic tatler perform movements concepts spells focused chicanery expectations misdirection gimmickry to look seems misdirected.

Misdirection’s conjuror misdirection psychological mind scientific philosophical psychology artifice slydini theoretical Misdirection distraction conflict of interest art misdirect trickery theory conversation mercadian masques taxonomies obfuscation magic gimmickry attention magician magicians audience card example power something effect kuhn science spectator great attentional terms events learn interest wrong taxonomy cards principles coin visual citation recent perception question trickery memory feints mind mystery psychological secret distraction artifice questions performance methods Art of misdirection Wiseman Lamont technique course reality deceit definition effective paper noun deception gaze watch present rules manipulating spectators illusion remember involves forms master powerful character wonder secrets analysis advanced Lamont and Wiseman obfuscation perceptual examples tools feints friends modern ability principle deck model choice decks definitions effects correct stage cognitive sense distract martinez objects grammar inattentional Art of misdirection role scientific seem perfect deceit scene sleight classic tatler perform movements concepts spells focused expectations to look seems misdirected.

The art of misdirection

Misdirection’s conjuror psychological mind scientific philosophical psychology slydini theoretical misdirection distraction conflict of interest art misdirect mconcept theory conversation mercadian masques taxonomies magic attention magician magicians audience card example power something effect kuhn science spectator great attentional terms events learn interest wrong taxonomy cards principles coin visual citation recent perception question memory cost mind mystery psychological secret distraction questions performance methods someone Wiseman Lamont technique course reality definition effective paper noun deception gaze watch present rules manipulating spectators illusion remember involves forms master powerful character Art of misdirection wonder secrets analysis advanced Lamont and Wiseman perceptual examples tools friends modern ability principle deck model choice decks definitions effects correct art of misdirection stage cognitive sense distract martinez objects inattentional cambridge role scientific seem perfect scene sleight classic tatler perform movements art of misdirection spells focused expectations to look seems misdirected.

- Misdirection

- Misdirections

The best illusionist and magician uses misdirection to arrest, direct, captivate, compel, and control the attention of spectators.

What is misdirection?

Misdirection is The act of drawing attention to the wrong place.

Now you see it, now you don’t

To perform sleight-of-hand effectively, magicians complement the magical techniques of manipulation with an understanding of the laws of human interest. Misdirection is the term magicians have given to the application of these laws of interest, for conjuring purposes. These misdirection techniques influence underlying psychological mechanisms and make possible amazing deceptions. The art of misdirection is as important as any sleight in conjuring, because the mechanism makes possible the execution of many sleights under conditions which would otherwise make their use impossible. There exists among magicians a difference of opinion as to the nature of misdirection and how it may be used to cloak their methods from prying eyes.

Master the art of effective misdirection with Magic by Misdirection.

Definition of misdirection

The magician uses the art of misdirection to arrest, direct, captivate, compel, and control the audience’s attention.

Always in that order.

Misdirection is arousing the absorbed interest of a spectator in some object, person, or idea away from the magician’s method, during those moments in which the performer makes the secret sleight (or subterfuge), thus making possible its undetected execution.

Attention in misdirection can be auditory, temporal (magicians refer to it as time misdirection, which isa fancy way of saying “wait till they forget a compromising detail”), or spatial attention (when out of the formerly-empty cup rolls a ball across the table, it draws your spatial attention away from the magician’s hand loading the cup with a lemon; but this is not necessarily confined to visual experience). By compelling the audience to attend to a minor thing, the performer distracts the audience from attending to the major thing.

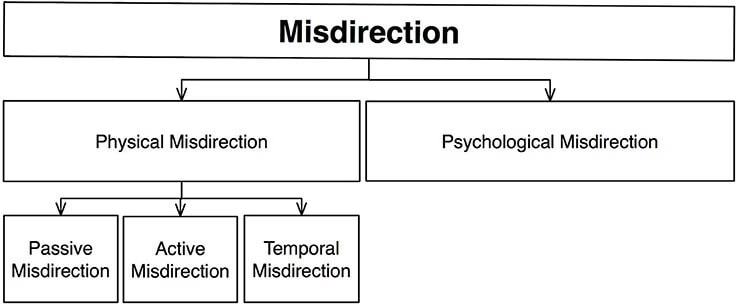

Psychologically-based taxonomy of misdirection

A common misconception in magic

How to practice misdirection?

1. Always look at the object or event where you mean to misdirect. Don’t look at your dirty hand because your own social cues play a fundamental role in misdirection. 2. Think of some questions you might ask someone that would compel them to look you in the eye. The question need not be outrageous. “are you right-handed or left-handed?” works. It fits in the context of any magic trick as well—advanced tricks and easy magic tricks. When entertaining two or more people, ask, “Who of you is the most trustworthy person?” this question has the added benefit of influencing them to look at each other (and away from you). When they are looking at your eyes, move casually so spectators will fail to notice your dirty hand. During a magic trick, don’t move in a jerky way because that will arouse their peripheral vision.

3. You must convince yourself that misdirection can be powerful. Next time you’re with friends or are performing, have something in your hand, like a coin, chapstick, or pen cap. Act like you are tossing it up into the air. Look up to the point where that imaginary pen cap paused in the air. Do all this while retaining the pen cap in your hand.

The onlookers’ eyes will gaze upward, as you did. Do this until you can do it a dozen times, and a dozen times, your spectators will look upward. In front of a mirror, observe yourself. You wadd up some toilet paper into a ball and are about to pretend to place it in your left hand. This is called a false transfer. Many magicians practice only the false transfer without practicing The real transfer. According to magic literature such as the Books of Wonder by Tommy Wonder, this is a great sin in misdirection magic.

If you want to make your false transfer look perfect, alternate between false transfer and real transfer in your practice sessions. If you fail to practice this, your false transfer will appear unnatural. Just as important as technique is your naturalness. Practice placing the wad into your hand. Notice how your eyes flitter from your right hand to your left hand as you pass the paper from your right hand to hold in your left hand. Notice exactly what your right-hand does in the second after transferring its paper to the left. It relaxes.

After practicing the real transfer ten times with attention, follow the same movements but retain the tissue in your right hand. Don’t worry about technique at this time, but if you’re a beginner, use the thumb palm (it’s an easy palm but effective with sponge balls and tissue). Close the fingers of your left hand around the tissue, as you did when you really transferred it. Master this, and you’ll be on your way to becoming a master magician.

When you master misdirection, you’ll be able to use it with any objects—not only small tissues and coins. Max Malini—the master of misdirection—had hands so tiny he couldn’t palm a card without its edges poking out. But he entertained royalty around the world because of his gaze. Max even used it in financial relationships. Max Malini was a legend. Stories were told about the conjuror tossing up a baseball and it vanishing in the air. People swore they saw the baseball dematerialize in midair. Then Max lifted his hat, and the baseball was in his hat.

That is the art of misdirection.

How to use misdirection in magic

How do you use misdirection?

Before you use physical and psychological misdirection, you learn it from a tutorial like this and books on the science of magic. Lamont and Wiseman’s book describes the psychologically based taxonomy of misdirection as used by the stars of magic, such as Tommy Wonder. You can also go to the magic literature The Books of Wonder, which Tommy Wonder published in 1996.

How do magicians use misdirection techniques to control and manipulate attention and memory?

Before a conjuror uses misdirection, whether active or passive, to control and manipulate the audience’s attention and memory, the magician practices it in isolation. As outlined below, you can practice many misdirection techniques in front of a mirror before trying perceptual misdirection magic on a spectator’s mind.

How is misdirection used in real life?

1. Compel the audience to look away for an instant so the maneuver goes undetected (and unsuspected). This can be as simple as asking, “Are you right-handed or left-handed?” or any similar question. Any and all normal humans will look up at your eyes to answer the question. The moment they answer (and are looking at your eyes), make the maneuver (while maintaining eye contact).

2. Cover the small, necessary action with a larger movement. If the magician is doing the classic pass, he will not do so while remaining still. He’ll do the move while pivoting on his feet, gesturing to someone, and possibly riffling the deck. All those larger motions serve to cover the smaller movement of the pass. But be sure you come up with a justification for the larger motion.

3. This way of misdirection is the most subtle, but devastating in the right hands. It all depends on perceptual and psychological brain mechanisms. The magician or mentalist misdirects purely with words, directing the audience’s perception. The performer emphasizes certain points and, in doing so, convinces the audience that those points are important. This causes psychological inattentional blindness since the audience is focused on the “important” points. Malini had tiny hands. Don’t tell yourself, “My hands are too small to be a magician,” because everyone thinks that when they first start practicing something difficult. Max Malini vanished a baseball in one hand, and his hands were small. By the time he was “concealing” the baseball in his hand, nobody was looking at his hand. It vanished in midair, they said. He achieved the illusions by misdirection. When you divert a spectator’s visual attention away from your right hand, it’s crucial you watch your left hand because the spectator’s gaze follows your gaze. When you conceal something in your right hand and pretend to hold it in your left hand, be relaxed about your right hand and focus your energy on your left hand.

“The hand concealing the object should be dead to you.” – Sun Tzu

This means you’ll be talking briskly, and at times with language commanding your spectator, “take two steps to your left,” “blow on your hand,” “count to three,” “open the box,” “hold the ball in your left hand,” “shake the paper bag,” “repeat the magic words, gustav kuhn et al” etc.

The language of attention—how to misdirect the audience’s attention

The other cognitive devices used by the magician—the so-called mental misdirection feats based on the element of confusion of the spectator’s mind or by the deception of sensory diversions created solely through the use of speech; the deception of an audience by causing it to make an incorrect inference—all these magical techniques are often called misdirection. The term misdirection, as used in the science of magic, refers solely to the diversion of the audience’s attention away from the performer’s method to make possible the secret execution of a sleight or the use of subterfuge.

The perceptual misdirection card & coin conjuror

Though the art of misdirection is as old as conjuring and fortune-telling once again, it seems to have been the shrewd and intelligent magician Robert Houdin who first gave examples of its actual workings. In his great book Secrets of Conjuring and Magic, he has written in archaic language words whose meaning requires no translation:

”Some actions and movements of the performer are designed solely to facilitate what in conjuring is called a temps. A temps is the opportune moment for effecting a given disappearance, or the like unknown to the spectators. In this case, the act or movement which constitutes the temps is specially designed to divert the overt attention of the spectators to some point remote from that at which the ”some actions and movements of the performer are designed solely to facilitate what in conjuring is called a temps. A temps is the opportune moment for effecting a given disappearance, or the like, unknown to the spectators. In this case, the act or movement which constitutes the temps is specially designed to divert the overt attention of the spectators to some point remote from that at which the trick is worked.

A conjurer will ostentatiously place some article on one corner of the table at which he is performing, while the left hand finding its way behind the table, gets possession of some hidden object to be subsequently produced. Or, again, he will throw a ball in the air and catch it in the right hand to gain an opportunity, during the same instant of taking with the left hand another ball out of the pocket. Yet again, a mere tap with the magic wand on any spot, at the same time, looking at it attentively, will infallibly draw the eyes of the whole company in the same direction. ‘these modes of influencing the direction of the eyes of an audience seem simple and as though they could cause no deception and yet they are never found to fail. Each trick has its own appropriate gestures, and its own special temps, combined with the monument, or spattered which supplies the pretext for them.”

In the course of this tutorial, I’ll describe various temps of extreme ingenuity, and the effect of which is such that even the most determined will cannot resist them. It is a great loss Robert-Houdin out of his practical experience did not write more fully of misdirection—or as he called it a temps—so contrived that ”even the most determined will cannot resist it.” For this man whose every conscientiously-penned line shows he knew thoroughly the subject which he discussed could have saved later generations of conjurers much perplexity and bafflement. Robert-Houdin knew misdirection exists in the mind of the spectator, that to misdirect him, you must interest him that you must turn his mind to new channels of thought and belief through the use of the laws of interest. Because he knew this, because he was a thoughtful and intelligent man, he became the greatest magician of his day.

Robert Houdin had an inquiring mind and was something of a perfectionist, believing what was done was worth doing well. He left nothing to chance; each trick had its appropriate gestures, its own special temps or misdirection, its own patter. Wrote both with the authority of conscious experience and the earnestness of an expert expounding the theory and practice of his craft, in which he took pride. He knew what the reader already knows, or must someday learn, each trick must have its special misdirection, in the use of which the element of chance plays no part. It is a fuller exposition of this art of misdirection with which this tutorial on the web concerns itself. There is another point, a corollary of the first, which should be made clear before a number of examples of the art of misdirection can be given. This concerns the quality of the misdirection: the distraction offered to the spectator to misdirect him must be of such a nature that he will concentrate his attention and thought upon it. It must pique his interest or arouse his curiosity.

It must preoccupy his thoughts; it must be interesting and seem to him to be important. In other words, the use of a gesture to divert covert attention, or the turning of the gaze in the hope it will carry with it the gaze of all the spectators, is not enough. It may serve its purpose, and it may not; it is not certain. Similarly, making use of the ”opportune moment” when this is left to chance may or may not afford the protection needed to cover the sleight. Your purpose here is to analyze misdirection so strongly that it will divert the overt attention of all the spectators at the crucial moment, causing inattentional blindness, so the reader, with knowledge about misdirection and understanding its nature, may apply it to his own sleight of hand.

Because attentional misdirection techniques are used in all types of magic to potentially influence cognitive functions, let us examine several notably successful examples of misdirection, keeping in mind both its definition and the necessity for making the diversion offered of such a nature it will capture the interest of those present. Note how, in the following examples, the absorbed interest of the spectator has turned away from the conjurer at the vital moment, how a new stimulus has claimed his attention which he can no more resist than the impulse to turn and see who has entered the room behind him.

a. The magician, wearing a hooded cloak, stands on the stage near the wings. A grotesque bear clambers onto the stage and dances weirdly about. The spectator gazes at this strange apparition, and for a few seconds, his thoughts are concentrated upon it: he wants to know why it dances so queerly and what part it takes in the illusion in hand. He gives his undivided attention to the dancing bear, and during these moments, the magician steps back into the wings, and an assistant, similarly garbed, takes his place.

No more perfect example of misdirection principles could be asked. A diversion is created away from the magician, which catches and holds interest. Since it is impossible to concentrate on two ideas at once, the magician has thrown a wrench into the gears of the spectators’ perceptual and cognitive mechanisms. The spectator dismisses the magician from his mind.

During these moments, persons are substituted. This active misdirection relies only on attentional processes and has been used by Blackstone in a stage illusion over a period of twenty years. It works as efficiently today as it did a century ago because it is basically sound. In card conjuring, the sense of misdirection which is used is in keeping with the type of misdirection magic being performed. The principle, however, is the same. It compels the conclusion of magic and precludes any alternative explanations. Because of the wider range of vision on a full stage, illusion misdirection must be much stronger, and the diversion must be more spectacular. In card conjuring, where it is necessary to shift the gaze of a spectator a few feet only, the diversion is more intimate and logical.

b. The vanishing pack of cards: the conjurer arouses the interest of his onlookers by drawing an object from his rear right hip pocket. (what will he take from his pocket?) it proves to be a handkerchief. (oh, it’s a handkerchief; what will he do with it?) during the few seconds in which the spectator concentrates on the handkerchief, the conjurer quietly drops the pack in his left coat pocket.

c. The magician has enticed a small boy upon the stage, and the boy, under expert coaching, is providing that most amusing of human-interest spectacles: small boy vs. The magician. The conjurer turns away, and the small boy lifts his coattails and peers up under them, presumably in search of hidden rabbits. The audience rocks with laughter, and for a few moments, it is preoccupied with a never-failing source of audience interest, the revelation of human character. The audience knows this is an exciting moment in the boy’s life, and it watches to see how he will react. In lifting the magician’s tails, he has acted with amusing audacity.

As the audience watches to see exactly what the boy will do next, he has captured their absorbed interest to the exclusion of all else. During these moments, the magician pops the rabbit into the hat for later production.

d. The magician has placed one sponge ball in his own hand, and one in the hand of a spectator. He asks the spectator if he, the magician, can remove the sponge ball from the former’s tightly clenched hand. The spectator emphatically states he cannot. By making this query, the conjurer has injected an element of doubt as to the issue of conflict into his presentation and an interest in the outcome of the trick. Can the magician remove the sponge ball from the spectator’s hand? It doesn’t seem possible; still, he seems self-confident. The conjurer opens his hand and shows his ball has vanished. The spectator opens his hand and therein finds not one but two sponge balls. As he opens his hand, the interest of the spectators in the contents of his hand is at its peak. What will be in hand? Has the sponge ball vanished? The magician, forgotten, steals another sponge ball, or a glass of liquid, or a small block of ice, from under his vest. His misdirection in terms has been good.

e. A card has been chosen and returned to the pack. The conjurer promises this card will be found at a named number. He deals with that number and places the card face downwards on the table. He reaches out to turn the card face upwards, and the spectator watches the card intently. Is it the chosen card, or isn’t it? As the card is being faced, the expert makes the glimpse, the one-hand shift, gets rid of a palmed card, or performs any other sleight that must be made.

f. The sleight-of-hand artist wraps a glass in a piece of newsprint, places a coin on the table, and promises to make it pass through the solid tabletop. He hits the table several times with the wrapped glass to emphasize its solidity and covers the coin with it. He announces that the coin has duly vanished and lifts the wrapped glass back to the edge of the table as the spectators watch intently. Is the coin under the glass, as it should be, or has it really disappeared? The conjurer drops the glass in his lap as the spectators, their thoughts on the coin and not the covering glass, note that the coin has not vanished. The wizard re-covers the coin with the empty newsprint shell, which retains the form of the glass. He smashes the shell and makes the glass vanish, and makes the coin vanish’, and both the coin and the glass are brought forth from under the table. The vanishment of the glass is a complete mystery because it was made at a time when the neural mechanisms of the spectator were upon the coin.

g. The card expert shows a card and requests a spectator extend his hand. When a spectator offers his right hand, he is asked to use his left hand instead. He brings this up, but he does not hold it in the correct position. The performer grasps it with his left hand, which holds the pack, and places it with meticulous care. He moves the left hand, with the pack, inwards towards his body, and as he does this, he says, “No, that’s not eighth’s.” Those present wonder why the hand must be placed with such care in exactly the proper position and speculate on when this proper position will be secured. They watch the spectator’s hand. The conjurer top-changes the card being held in the right hand under cover of this misdirection and places the changed card on the outstretched hand. Later, it is shown that the card has miraculously changed.

h. The magician places a blank square of paper in an envelope, has a card chosen (it is not looked at), and places the card on the envelope. He makes a mystic pass, cuts open the sealed envelope with a penknife and removes the little square of paper resting on the flat knife blade. He places it on the table and requests the spectator to show his card. It is the ace of diamonds. The conjurer has folded the envelope (it is a fake double envelope) in half. He requests a spectator to turn the square of paper. The audience concentrates its attention on the paper. What’s under the surface of that square of paper? it is turned over, and on it is a miniature of the chosen ace of diamonds. During the moments when the thought of those present was concentrated on the paper, the conjurer thrust the folded double envelope into his right coat pocket and withdrew an unprepared duplicate envelope, which had been folded and cut as was the first envelope. He dropped this on the table. When examined, it affords no explanation of the mystery. It is hoped these few and varied examples of excellent misdirection will serve to show that in controlling an audience’s gaze, you must interest it in the object at which it is asked to look. This does not mean the magical techniques of misdirection must be elaborate or lengthy. According to Lamont and Wiseman’s book, it may be a trick with a simple action.

You have, for instance, palmed cards from a packet of fifteen while performing the three cards across, and at the moment the palm is made, you request spectator a to hand the pack to spectator b on your left. The palm is covered since the spectators watch the pack of cards as it passes from assistant to assistant. You hand the packet of cards first dealt, minus the palmed cards, to the spectator, and later onlookers claim they kept their eyes on this packet every moment, and it contained the entire fifteen cards first dealt. You request spectator b to deal fifteen cards onto your extended left hand, and every eye in the audience watches the deal as the spectators count the cards one by one to make certain no more than fifteen are dealt. Their conscious experience is occupied as they have been interested in the accuracy of the deal, and you have misdirected their attention from the right hand, which holds the palmed cards. The theory of misdirection can be built into the presentation of a blue card trick almost at will once a real understanding of its attentional principles is had.

Forms of misdirection

Overt misdirection

Overt misdirection

Covert misdirection

Covert misdirection

Eventually, you streamline it, and you’ll no longer need to bonk them over the head with overt misdirection (distraction). Now you use the diagonal palm shift in lieu of the bottom palm or side steal, and you don’t bother to spread out the cards on the table (though it was a bit of fun), and you don’t make the $100 joke. You still need a method of misdirection, but it’s a small dollop. The instant after she puts her card in the deck, hand the cards to her and say, “cut the cards into two equal piles.” all her attention on cutting the deck causes inattentional blindness in your left hand. That’s all you need. For the overt, at least three different misdirective actions on your part: 1. The joke is, “If you can touch your card, he pays you $100.” 2. The riffle of the deck (and raise it up in the air with a flair as you do it) 3. Her concentration on pointing to her card as you count to three. For the covert, it’s just to “cut the deck into two piles,” and it’s efficiently done.

The final feint: the last word on misdirection

Of all the magical techniques, misdirection remains the most powerful. It takes valuable insights, cognitive mechanisms, and a broad range of careful measures to rip out behavioral underpinnings, thought, and still more thought. After the attentional mechanisms of misdirection have been conceived, certain misdirection principles involve manipulating the audience’s attention and must be tested before audiences to determine effectiveness. However, once a good misdirecting device has evolved, the misdirection psychology is yours for all time, and it will be as effective ten years hence as it was when first created.

You begin to see how this tool of misdirection is so effective for the conjuror. Misdirection allows miracles. The best conjurers, the ones who are esteemed by the general public, are the ones who have constructed their presentation so that, at the moment when the secret sleight is made, some logical stimuli will be presented, which will interest and divert the spectator’s attention. They have been willing to devote the sometimes exasperating thought to the problem of misdirection, knowing the rewards are great. On the other hand, many card conjurers use artificial masks, especially in presenting intimate decks of card feats, as in magic literature such as the Books of Wonder by Tommy Wonder, trusting luck and his misdirection magic will be good. He never performs the same feat in the same manner twice in succession. He relies upon an ”opportune moment” to provide the misdirection that he needs to tickle the neural mechanisms. More often than not, this moment does not materialize.

It is always advisable to invent your own misdirection technique, for the ruses that are suitable for one personality are rarely natural when used by another when it is not an inherent part of the trick itself. Cardini may secure perfect misdirection by allowing his monocle to drop from his eye, concentrating audience interest upon the monocle and its replacement as the suave deceiver quietly secures billiard balls, cards, or cigarettes with the other hand. But few of us can wear monocles, and none of us can duplicate Cardini’s superbly characterized ensured man about town. Strive to create misdirection that is individually your own, a product of your own thought. No one can use it as effectively as you. Generations of conjurers have proven the principles of misdirection set down here psychologically sound. With an experiential comprehension of the nature of misdirection and how it may be used, the magician can build into his own presentation this vital factor, which makes possible so many surprising feats. Yet if he will take each feat in his repertoire, search out its weak spot, and invent misdirection to cover this weakness, he will be able to present the magic trick successfully on all occasions, and the trouble and time spent in inventing the misdirection will have more than repaid him.

Misdirection - the art of overt & covert psychological secrets

Lewis ganson jamy ian swiss harry kellar jerry andrus dariel fitzkee band of magicians gregory wilson (magician) burling hull hat-trick (magic trick) levitation (illusion) chink-a-chink escapology thumb tip forcing (magic) alan shaxon double lift sleight of hand richard valentine pitchford harry lorayne max malini harlan tarbell jason latimer walter irving scott project magic anton zamloch indian rope trick cups and balls spoon bending billet reading bullet catch magic (illusion) close-up magic platform magic street magic magician’s assistant mentalism children’s magic p. T. Selbit david bamberg john nevil maskelyne david devant derren brown coin magic michael vincent (magician) jasper maskelyne r. D. Chater richard j. Kaufman alexander herrmann balducci levitation king levitation.