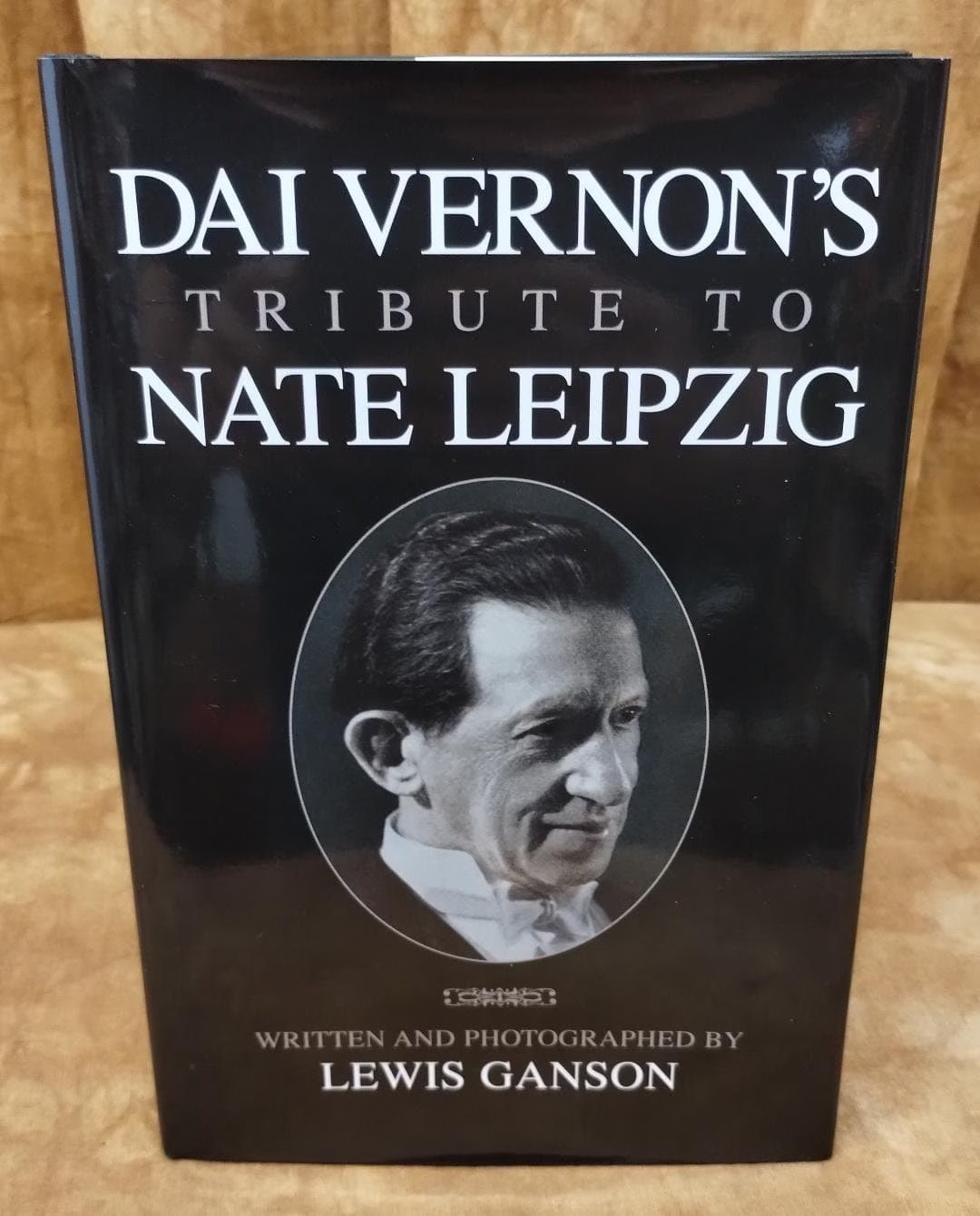

To obtain a true understanding of the methods used by a certain magician, it is helpful to appreciate why those methods are effective in that person’s hands. His personality, appearance, character, and general outlook on life all play a part in determining the type of subterfuge with which he can best decide to even audience., two performers with different personal characteristics may be able to use similar methods, but each will develop different techniques and their employment. In Tribute to Nate Leipzig, Dai Vernon gives us a good example of this in his comparison of three of the greats of magic history—Nate Leipzig, Max Malini, and Paul Rosini. He tells us that where Malini was harsh and challenging, colorful and bold, Nate Leipzig was quiet, gentle, soft-spoken manner and voice, and gave at all times the impression here was a gentleman it would be pleasant to know better. Judson Cole said, few acts have real authority. Nate had it, plus Intangible glamour which has been called everything from stage presence personal magnetism; but, call it what you will, he electrified in audience when he walked out on stage. The different backgrounds of Malini and Leipzig were reflected in their magic. Malini started by busking in saloons; a hard school in which he developed an crass approach to mankind. Leipzig first worked as a lens maker—a quiet and contemplative way of making a living. The influence of his background on his magic can be summed up in his own words when he said

“Oh, I’ve been doing magic for 50 years. An audience like to feel that a gentleman has fooled them.”

On another occasion, Nate Leipzig said:

“If they like you as a person, they’ll like your act.”

Both Max Malini and Nate Leipzig played before large audiences in all parts of the world, and their public acclaim and fame were the results of these performances; but they were close-up magicians. Both are now remembered best for the seemingly impromptu miracles which they would do off stage, under the closest scrutiny of keen observers. My favorite little Leipzig miracle was when he used to borrow something common and familiar, a bit of cigarette paper. Then Leipzig folded it two or three times, and finally the folded paper turned into a white butterfly and flew away. Now let us study briefly the circumstances which determined Leipzig’s background, according to Dai Vernon’s Tribute to Nate Leipzig.

Birth of A Magician

Horace Goldin appeared at the Detroit Opera House and gave one of the finest magical performances Nate had seen. One evening at Geese’s restaurant, Nate was introduced to Goldin as the “local Magician” by one of the city’s leading merchants. Asked by Goldin what he could do, Nate performed a coin roll, then went on to show some of his pet card tricks. In return, Goldin did a few pocket tricks extremely well, but then Nate had the great satisfaction of fooling him completely. In Nate’s own words,

“We were drinking beer I asked Goldin for a penny. I told him to see It was perfectly dry, then to take it by the sides and drop it into my glass of beer in such a way It would drop perfectly flat in the bottom of the glass. He did then I proceeded to tap the glass with my finger, when the penny floated up to the top of the beer. I was satisfied when I heard Goldin say, “Do that again!”, for Is a magician’s reaction when he is beaten.”

Leipzig first experience of performing on the professional stage was his last, and change the course of magic history. The manager of the Temple Theater called Nate and asked him if he would stand in at any time any book act could not appear. When such an occasion arose, Nate obtained permission from Max Rudelsheimer and went on with the understanding it would be for a few days only. Nate later confessed he never realized the difference between the amateur and professional until then. Being a local boy, Nate Leipzig went over well for the first day, but the Sunday audience was a rougher type, especially in the gallery. They liked the act which preceded Leipzig, and hooted and yelled for an encore. Nate spent the most miserable fifteen minutes of his life. On that night, all ideas of making show business a career were swept from his mind. A meeting with a magician named Adams started Nate using thimbles, as Adams showed him a few moves which were good. Nate made up some metal holders to hold the thimbles, he could make the full production. By exchanging ideas, a full thimble routine was worked out, and it was this which eventually formed the basis of Leipzig’s stage routine. After working 17 years with Max Rudelscheimer, the optician, Nate became dissatisfied with conditions and made up his mind to leave. Even he had no idea of going into show business, though his great love was going backstage at the Temple Theater to meet the performers. He was eventually persuaded to join the Berol Act. Felix Berol and his brother Willie had an established act, making rag pictures on stage. They were about to split up and Felix offered Nate a half interest in the act. They started out in New York, then found that Willie Berol had decided to take a lady partner and do the same act, using the same name, which he had a right to do. Neither act did well, and both struggled along for about six months. Felix decided to do a solo memory act, Nate joined forces with Willie. The arrangement was not successful, and, after a while, they gave up. Nate was determined not to be a failure, and concentrated on private work with his magic. He went to all the leading agents in town but had a rough patch for several months. When Nate Leipzig was down to his last two dollars, he met Alfred Guissart, an architect and amateur magician, who asked him to be his guest that night at a dinner at the Elks Club in New Rochelle. After dinner, there was entertainment and Nate was persuaded to perform. He did some of his favorite effects and was called back several times. That evening was the turning point of his career, as he began to get calls from agents offering him private work. Soon he was making forty to fifty dollars a week—fifteen dollars from an agent was at that time the average fee. Nate Leipzig had designed his performance for private engagements, and at first did not consider that his material was suitable for vaudeville. A favor he did for J. Warren Keane showed that the Leipzig brand of magic could prove extremely popular with theater audiences. It happened that Warren Keane was playing Proctor’s 5th Avenue Theater, but wanted to sail for Europe on the Saturday. He had permission to take time off, providing he could get someone to deputize for him. He approached Nate Leipzig to take his place at Proctor’s for the Saturday and Sunday shows. Nate maintained he did not have the right type of act for this work, but Warren Keane insisted that the tricks which Leipzig performed would be a big success. Leipzig eventually accepted, but it was in fear and trembling he stepped onto the stage on that Saturday afternoon. Nate Leipzig need not have worried; for, he was due for a pleasant surprise. As he was leaving the theater by the stage entrance after his first stage performance, two messages were handed to him — one from William Morris, one of the biggest agents even in those days, and the other from the man who booked the Proctor circuit, Jules Ruby. Nate called on the two agents and was offered engagement by them both. Nate finally accepted a short tour for six weeks on the Keith circuit, booked by William Morris. Within weeks his salary was twice raised and he knew that, in addition to his private engagements, he had another medium for his magic. Leipzig was a close-up performer. It did not matter he worked on a stage, his personality in presentation were those of a close-up worker. After walking on stage, he established himself in the eyes of the audience as a magician with a thimble routine. The rest of his act was performed for a committee from the audience which joined him on stage. The effects Nate obtained we’re seen by the audience through the eyes of the committee — it was impossible for all the audience to see the card magic because they could not see the faces of the cards used, but they were amused by the reactions of the few people in the committee. The amazing thing was that Leipzig enchanted the audience with a few thimbles and a pack of cards—but then the principal magic was Leipzig personality, charm, and complete hold he had over his audience. To center all attention on what he was doing, Leipzig had a spotlight focused on the small objects he was handling. This was In all his contracts Leipzig stipulated he must have a spotlight from the front of the house. In America, this was usual practice; but, in Europe, the spotlights came from the wings or the sides of the stage. This was fatal, as the light striking his hands from the sides cast a shadow over the small objects. Many theaters had great difficulty in arranging for the special spot light, but since it was one of the conditions of the rider, it had to be fulfilled. At The Palace Theater, Cork, the best that could be arranged was to have a boy holding a light in the orchestra; then came the other extreme at the Zoo Hippodrome in Glasgow, where a special platform was built over the orchestra leader. On the platform was an object like a cannon; when this was switched on, Leipzig felt he had been shot—they had borrowed a searchlight from a ship! The light was strong that Leipzig could hardly bear to work with it on. It was such insistence on these aids which helped Leipzig to put over his act— there is no doubt at all that the one big factor in his success was Leipzig himself. Leipzig traveled the world with his magic, being popular in Britain, Australia, south Africa. Wherever he went, Nate Leipzig was accepted in all circles. His gentlemanly bearing and charming personality, endearing him to all with whom he came into contact. He had the unusual honor of appearing before two Kings and Queens on the same occasion. On the 9th of June, 1907, their Majesties, the King and Queen of Denmark were the guests of King and Queen at Buckingham Palace. Leipzig was commanded to appear before them. Other members of the royal family were present, including the Prince of Wales. Leipzig was the only professional artist who was not a member of the legitimate stage to be accepted at the exclusive Lambs’ Club. He was the first magician to be presented with the Gold Medal of the Magic Circle—inscribed, Presented to Nate Leipzig by the Inner Magic Circle, April 11th, 1907—for good fellowship and originality. Dai Vernon tells us of Leipzig the below.

“He was deadly sure and every trick he did. Every trick he performed had been carefully analyzed, if weak points concealed as to seem like strength—nothing was left to chance.”

As an example—Leipzig never fan-forced a card in his life. The only force Nate used in his public performance was one where in he kept a break, riffled the pack, and had a spectator put his finger into the pack as a riffled. Leipzig shoved the opening in the pack onto the spectator’s finger, guaranteeing success. Leipzig guaranteed the success of his methods by simplification, timing, and strong misdirection. Nate did not use difficult sleights. Indeed, he used comparatively few sleight. Preferring the subtle move in place of manual dexterity. Nate Leipzig earned a reputation for great manipulative skill; indeed, his early advertising material carried the statement, The Phenomenal Digital Expert and Premier Manipulator of U.S.A, but the facts are he avoided any method that had the slightest chance of failure. Leipzig had two rules which all magicians should heed—if their attention palls in the slightest, change tricks quickly. And, more important: don’t ever perform unless coaxed. Leipzig realized that people may ask to see a magic trick out of politeness, but would not press the point unless genuinely interested. Everyone who knew Nate Leipzig remembers him as a gentleman in the true sense of the word, for he had the real kindness Is such a basic component of true gentility. This is exemplified by the occasion when Dr. Daley sat next to Nate during a performance by a magician who had stolen every trick from Leipzig. At the conclusion of the performance, Dr. Daley said: “Nate he did your act!” “Yes,” said Leipzig, “but he did it well.” In 1903, Nate stepped off the boat in England and met Leila Bevershansky. Leila was born in Birmingham, England. Nate was born 1300 miles away in Stockholm, Sweden. After this serendipitous meeting in England, the two lovebirds soon married. Leipzig made a wise choice when choosing a wife; for, in addition to being an ideal partner, Leila helped Nate in his work — especially from the business angle. It is likely that Nate Leipzig is no more than a casual name from the past. The fact is that at the time of his death in 1939, Nate Leipzig had a reputation for being one of the finest, if not the finest, sleight-of-hand performers of his time. In his introduction to the English edition of Ottokar Fischer’s popular book, Illustrated magic, Fulton Oursler wrote that,

“The king of manipulators. Will always be Nate Leipzig. There’s something Mephistophelian about this astonishing character. If I were told to his name were Dr. Faustis, I should believe it. He is the Paderewski of card manipulators, the Paganini of magicians, the virtuoso in whose hands the playing cards become not pasteboard but living creatures obedient to his commands. Whenever I see Leipzig with a pack in hand, I expect the cards to burst into song.”

Oursler was not alone in his opinion. Wilfred Johnson wrote that:

“The incomparable Leipzig was known as a magician’s magician. As well as a headliner on the leading vaudeville circuits. Leipzig’s card creations have become classics, and his consummate skill is legendary in the art of legerdemain.”

Will Goldston believed Leipzig to be the finest card manipulator he had ever seen, and Henry Ridgely Evans wrote that Leipzig’s art was subtle and undetectable, and he was pre-eminent in his country and perhaps the world. The World Press wasas complimentary, with newspapers in New York, San Francisco, London, Melbourne, and Johannesburg proclaiming him the most expert prestidigitator in the world. This skill is verified by the fact Nate Leipzig was the first magician to be awarded the Gold Medal of Magic by the Magic Circle of London, in 1907. Nate Leipzig was one of the best loved of all magicians, revered by his fellow conjurers and non-magicians alike. He was a kind gentleman and a great humanitarian, says Dai Vernon. Vernon states that Leipzig was liked by everyone and in turn never was known to speak disparagingly about others. One time when Vernon was sitting with Dr. Daley and Leipzig Watching Ted Annemann do a trick, the trick he was doing had been stolen, lock, stock, & barrel, from Leipzig. Dr. Daley commented, “Nate, he’s doing your three pellet trick. Exactly like you!” To which Nate replied:

“Yes, but he’s doing it well.”

Vernon relates how Leipzig would gently admonish magicians who were of youngsters and less adept magicians by saying:

“He’s only a young boy. When some of you fellows were young, you had to work at it, too. I can see he has the touch. He’ll learn.”

In May of 1938, Nate Leipzig was elected president of the Society of American Magicians. He was one of the most popular presidents ever, and when the S.A.M. Published the trial issue of what would become their journal, M.U.M., Nate Leipzig was featured on the cover. Editor Vynn Boyer wrote that, under Leipzig’s guidance the Society reached the highest plane of its tranquility. He was beloved by all, both young and old, and he will be remembered by all, for the great man he was. Nate Leipzig was born Nathan Leipziger, in Stockholm, Sweden, on May 31st, 1873, one of eight children. His father emigrated from Russia to Utica, New York in the late 1850s or early 1860s, where he met and married Nathan’s Mother. After a few years, they moved to Sweden, eventually settling in Stockholm, where they lived until Nate approached his teenage years. At that time the family moved back to the United States, with most of them settling in Detroit, Michigan. Education and cultural arts were important to the Leipzig or family. Most of the children received good schooling, and there was always good music in the home. Several of the siblings developed a talent for drawing, and one of Nate’s older brothers became a successful newspaper cartoonist. Nate developed an early interest in magic, most probably from his mother’s oldest brother who had once been with the circus and who sometimes did tricks for the family. Through diligent practice, Nate himself became proficient with numerous pocket tricks, which he performed for friends and relatives. Because the family suffered from financial difficulty, Nate went to work at 12 years of age as an errand boy for the firm of L. Black & Co., opticians. A year later the company moved him into the factory where he learned to grind lenses and repair all kinds of optical goods. Then, a short time later, Nate left Black and Company to go with another optical firm where he worked for seventeen years. Magic, then, was a hobby for Nate Leipziger, one that became all-consuming. Before long, he was performing frequently for community groups social events, gratis. Borrowing a few mechanical tricks from a friend, such as the Spirit Slates and the Nest of Boxes, Nate developed a competent show which, coupled with his pleasing personality, made him a favorite in the city. In time he received five or ten dollars for some of the shows, which was a welcome addition to his modest salary. Nate tells a humorous story of performing for a local neighborhood club that had a reputation for not paying their performers. Before the show, Nate went to the chairman and asked to borrow $10 for used in the money catching trick, The Miser’s Dream. The money was loaned, and Nate was assured his $5 fee! Detroit was a major city, and most of the top entertainers of the day performed at the Detroit Opera House, or the Temple, or Wonderland Theater. The first major magician Nate remembered seeing was Alexander Herrmann, whom Nate claimed to be superb. Nate wrote in his autobiography, “It was a marvelous evening, there never was anyone to equal Herrmann in his own style of magic. He held you by his appearance alone the moment he stepped onto the stage. The first thing he did stumped me completely. Smiling at the audience he showed his wand, ran his fingers along it to the top and there appeared a real orange! He kept a vein of humor running through all his tricks.” In the Vernon tribute to Nate, Dai recounts that a colleague at work gave Nate a copy of The Secret Out, an out of print magic book published in England. After reading and mastering the rudimentary sleights contained in that book, Nate recognize that others had read such books, and it was likely that some spectators could follow what he did. At that time Nate determined to invent new and original methods for doing those and other tricks, and after considerable considerable time and effort he succeeded in this aim.

“To that alone, I attribute my success, since for many years my peculiar methods remained unknown and I was able to fool the magicians as the public. Many years later, when I had become a professional, my brother artists called me the magician.”

Though he performed some paid shows, his greatest pleasure came from joining the fellows at the Local Tavern for a few beers, entertaining them with his tricks. He recalls seeing one magic trick performed there by a gypsy woman he never figured out. The woman asked the bartender for a thin-walled beer glass. She took it, showed it around, and covered it with a handkerchief, twisting the excess cloth around the bottom of the glass. Holding it upside down, a strange thing happened. There was a hissing sound, like the bubbling of an Alka-Seltzer, but much louder, and the glass begin to vibrate violently. When the hissing at vibration stopped, the handkerchief was flicked open, and the glass had vanished! Nate took every opportunity to watch professional magicians work, and usually went backstage after the show in the hope of meeting them. Once he had shown a trick or two of his own, to prove he was a magician, those magicians usually opened up to him, and many friendly acquaintances were made. His own magic education was expanded through the sharing of Secrets. Because Nate had devised many of his own moves, especially with cards, which was his favorite magic, he was readily accepted. Nate Leipziger became well known in Detroit he was invited to watch entertainment from backstage at the major theaters. In this way, Nate many famous magicians, such as Harry Keller, Howard Thurston, Carl Jermaine, or is golden, Leon Herman, Houdini, Le Roy, Talma and Bosco, and many others. It was in this way he learned the double lift, a new and Innovative Concept in 1900, and one of his Fondest Memories was meeting and becoming friends with the famous Japanese magician, Ten Ichi, who traded his classic thumb tie for Leipzig method of working the ring on the stick. He learned a powerful lesson in misdirection from watching the Ten Ichi show. At one point in the show a Japanese girl came on stage with a drinking glass, which she showed empty and placed on a small stool. She then went into the audience, produced a coin from a coin one, and apparently tossed it toward the stage, where it was heard to land in the drinking glass. This was repeated five more times. She then went back on the stage and slowly poured six coins out of the glass. This magic trick fooled Leipzig badly the first time he saw it. The second time, you learn the subtle secret. When the girls first went into the audience, followed by the spotlight, all eyes were on her. At that moment, and assistant walked slowly by the stool and drinking glass and loaded 6/2 dollars into it into the glass. He then stood off stage with another glass and six more coins, which he dropped one at a time into the glass each time the performer supposedly tossed a coin toward the stage. Though equally important were the lessons he learned from non-magic performers. In a short article in the January, 1939 Sphynx, written while he was president of the SAM, Nate wrote he strongly recommended to those who wanted to make magic a career they study voice, pantomime, and stage deportment. He, himself, had learned such skills from Henry E. Dixie, one of America’s outstanding actors in the 1890s, and singer Herbert Watrous, who taught him how to make his voice carry to the top gallery. Nate wrote:

“I learned from actors presentation, and without proper presentation the best sleight-of-hand is nothing but a juggling feet.”

Indeed, Fred Keating, Leipzig’s protege, was to say of Leipzig:

“Nate neither juggled nor manipulated. He caressed the cards, he whispered to them, he enchanted them, and thereby drew from them mystery, drama—never card tricks.”

Nate always claimed that those lessons prepared him for success on the stage. During these formative years in Detroit, he became friends with Merril Day, a youngster about his own age, who performs some of the prettiest coin work that Nate had ever seen. The two decided to meet weekly, and each was charged with coming up with something new and original every time. Wrote Nate, “It was at this time I figured out my best effects, which I have been doing ever since. One day while holding a vest button in my hand, I tossed it in the air and caught it on the back of my hand, which being rounded on one side caused it to roll accidentally across my fingers. I was surprised I tried to do it again, but without success until I placed it on the back of my hand by moving my knuckles made it roll over and over.” For three years Nate Leipzig worked New York City on the east coast, in Vaudeville, and for private parties he worked his card magic and other bits. His list of friends grew as he frequented SAM meetings at Martinez, including Theo Bamberg, Clement de Lion, and many others. Then he moved to London with a four-week engagement at The Palace Theater. In London, he spent as much time with the members of the magic circle of London as he had with the Saturday nighters at Martinka’s in New York.

“I reveled in the performances of David Devant, one of the finest entertainers in magic I ever hope to see. Even more than his magic, his style of presentation stood out. He had magnificent stage presence.”

Dai Vernon’s Tribute tells us that, always, Leipzig studied the performance style of magicians and other entertainers. That was the to his own success.

This was the origination of the famous coin roll or Steeplechase, and Nate Leipzig was to become the master of this flourish that had that has been in the repertoire in every coin master since. Several of his original cards lights became standard work for card magicians, as well, and he is generally credited with having invented the Side Steal. Enough, a few years later, Nate performed this trick for Alan Shaw, who was second only to T. Nelson Downs as the foremost coin man in the world. The following year, Horace Goldin, visiting Detroit for the second time, told Nate Howe Allen had perform the coin roll for him, but did not have Nate skill. Alan had claimed it as his own origination, but golden stopped him cold by saying, oh, I see you have met Nate Life sticker in Detroit! By the time he was in his mid-twenties, Nate’s reputation as an excellent sleight-of-hand artist had spread far and wide. One evening, Nate was backstage performing his coin roll for a friend and another performer Nate did not know stopped and said, you are that fellow I heard about in London. Tommy Downs was telling me about you. Nate had not as met T. Nelson Downs! At 29 years of age, Nate was persuaded by Felix Berol to go into partnership with him to continue a rag picture act that Felix and his brother had performed with some success. The brothers had quarreled and split up, and Felix was looking for a partner. Felix claim that the actress saved $150 a week, which was good money then. In 1902, Nate Leipzig—the name he took for stage work—moved from Detroit to New York City. Felix soon and introduce Nate to Sargent the magician, the same John William Sargent who helped found the Society of American Magicians in that year. Sargent spread the word about Nate Leipzig, and Nate soon found himself the center of attention in Martinka’s little back room on Saturday nights. It was there that the S.A.M. Was founded in May of 1902. The act did not do well. Felix’s brother continue the act, under the same name, and there wasnot enough work for two such acts. Leipzig had a difficult time of it for several months and was finally down to his last two dollars. Through the S.A.M., Leipzig had met a New York architect an amateur magician, Alfred Guissart, who invited Nate to be as guest at an Elk’s Club dinner. The Exalted Ruler of that club have not arranged for a lot of talent, and ask Guissart if he could impose on Leipzig to do a few minutes. Leipzig di. And was a tremendous success. The Elk’s Club offered him fifteen dollars for his services, and Leipzig’s career as a society magician was born. Through his society engagements he gained a considerable reputation for skill and ingenious presentation, and was asked to take Warren Keane’s place at Proctors 5th Avenue Theater for the final two days of that performers contract. He did happened to be observed by several Vaudeville agents, including William Morris, one of the biggest agents even in those days. That led to six weeks on the Keith circuit at $50 a week, which was more than most performers received for their first Vaudeville bookings. Leipzig explained to William Morris he, Leipzig, had not sought out Vaudeville, and he earned more than $50 a week doing private parties. As much as they liked him, magicians In 1902 predicted that Nate would fail on the Vaudeville stage. No one has ever attempted big-time theater with a card magic act! Nate’s approach was to invite a committee from the audience to be the eyes for everyone in the theater. Know the audience cannot see the cigarette paper or the face of the cards, they were amused by watching the reactions of the few people on the committee. His major secrets were his charm, personality, and the complete hold he had over his audience. These one him constant a claim, and Morris raised his salary twice during that first year. Nate Leipzig was possibly the first performer to use motion pictures in his act. At the close of his show, he will perform the coin roll, accompanied by a film showing his hands in close up, thereby making it possible for everyone in the theater to see his artistry. While in London, Nate Leipzig became a popular society performer, when he was not turning a cigarette paper into a butterfly and working the music Halls, and in 1906 he was invited to be one of the acts on the magic circle’s first Grand magic science, which was held in St George’s Hall courtesy of the Maskelynes. A year later, he was awarded the first gold medallion ever presented by the magic circle, a testament to his skill as a performer. Many other honors came to Nate Leipzig during these early London years. He performed both on the continent and in London for royalty, including Edward VII and queen Alexandria and George V and Queen Mary of England, Empress Eugenie of France, the king and queen of Spain, and the king and queen of Denmark. The magician’s talents took him to Europe, South Africa, Australia, Canada, and San Francisco, before he returned to the United States to settle with his wife, Leila, whom he had met the first day he stepped off the boat in England, back in 1903. Though he continued to play both sides of the Atlantic into the 1920’s, New York city became Leipzig’s primary performing area, and he and Dai Vernon, 20 years his Junior, became the preferred society magicians, booked to perform for New York’s rich and famous by Francis Rockefeller King, perhaps the foremost private booking agent in New York. Nate continued to be heavily involved in both professional and amateur magic throughout his life, and by 1932 became one of the five original members of the New York Inner Circle, the others being Al Baker, Arthur Finley, S. Leo Horowitz, and Dai Vernon. In 1938, he was named one of the 10 living Card Stars, the others being Annemann, Al Baker, Arthur Finley, Cardini, S. Leo Horowitz, Stewart Judah, Bill McCaffrey, Paul Rosini, John Scarne, and Dai Vernon. Because of his long-standing affiliation with performers in all areas of show business, Nate Leipzig became a valued member of the famous line Lamb’s Club in New York; he was the only professional artist who was not a member of the legitimate stage to be accepted into that club. He frequently went to the club, sharing beer and card tricks at the bar with old friends; this became a enjoyable part of his of his life. Nate Leipzig took pleasure and helping others. He was instrumental in the professional growth of Fred Keating, who became an exceptional performer in the 1930s, 1940’s, and 1950s, and magic and on the legitimate stage, and the famous cardmaster, John Scarne, publicly and not acknowledged Nate Leipzig, saying:

“Whatever I can do, is because Nate Leipzig showed me how to do it.”

In May of 1938, Leipzig became the popular president of the Society of American Magicians in magic history. Part way through his term he began to show the effects of the cancer which was to take his life. He still performed at the National Conference of the S a.m. In New York City on May 29th, 1939, two days after he passed the presidency on the Shirley Quimby. On October 13th, 1939, he passed from this life. And, then, obituary, John Mulholland, the esteemed editor of the Sphinx, wrote: “Nate Leipzig was a cultured gentleman, a clever raconteur, most loyal friend, and the wise and helpful advisor of countless young magicians. He never spoke or thought in an unfriendly manner of anyone. He was never busy to give his valuable services to a worthy charity, nor aid and counsel to one in need, nor give advice for magicians. He stood as a model of conduct for magicians to follow.”